Detail of paint experiment of a still life with James Bland, oil on paper

13th December 2024, James Bland

My first studio visit is in December to James Bland in Cantebury. James works from a large spare bedroom in his house. It has a beautiful bay window, that I think is perfect, but he has covered it in a white sheet to diffuse the light. His studio consists of an easel, an old chair, a couple of vases and a lamp. I immediately sit on his floor and he joins me there and we chat about painting and compare our different brands of paint.

James’ paints are mostly smallish tubes of good quality oil paint, Michael Harding and such, in a range of colours - including many secondary, earth colours and black. He mixes his paint with a palette knife on a flat surface about the size of a chopping board and thins it sparingly with Zest It. In contrast my paints are student quality, in massive tubes and missing all their lids. I thin my paints with a concoction of mostly linseed oil, thinner and a tiny bit of varnish, that I’ve mixed together in random volumes. I mix with a brush and use microwave curry containers as palettes.

James is interested to compare our Viridian Greens and he shows me how much more sophisticated his is (he is not wrong). He sets up a still life for me to paint and we chat while I work. James asks if he can record our conversation and he sets his phone up to make a video while we work. He talks about how he can tell that I’m a floor worker and notices how I am using one of my feet to hold the paper I’m working on still (which I hadn’t really consciously registered). He says when he’s painting people it’s important to see the back of their head too, so that you can create that sense of the three dimensionality of them.

He introduces me to a Michael Harding Lemon Yellow, which I think is the colour of butter icing, and we have a discussion about if I don’t use black then perhaps I shouldn’t use white either. I take this literally in the weeks after this, which I will waffle on about another time. During this time James makes the amazing portrait of me, using a random colour palette that I partly forced upon him, and includes some of his paints and I think one of mine. And he does jump up and wander behind me from time to time. I am astonished that he can do this while we chat.

Mixing up paint using various limited palettes following my visits to James Bland and Arthur Neal, oil on maxi pad paper

14th December 2024, Arthur Neal

The following day I visit Arthur Neal in the coastal town of Deal. Arthur meets me from the train station and we wander through Deal via Linden Hall Studio where we are both showing work in their Winter Group Show. Arthur knows the gallery well and the owner jokes that whenever they need a spot filling they just bung one of his paintings up. While we’re there a member of the public visiting the gallery stops Arthur and tells him how wonderful he is and how much she loves his work. He is very humble about the whole thing. I feel like I’m hanging out with a celebrity.

Back at Arthur’s house he has made mushroom soup and I meet his wife Jane who is writing Christmas cards that have been designed by Arthur, a woodcut of a camel, they’re strung up around his living room drying. Arthur’s garden studio has wonderful natural light and, like his home, is filled with his paintings, drawings and books. His paint palette is a white table top - at counter hight and he has his colours, two of each primary (warm and cool), plus black, white, Viridian and Yellow Ochre, arranged around the edge with a vast area in the middle for mixing. He uses Cranfield oil paints, which he buys in large tins and decants into jars. I mention the Michael Harding Viridian Green - Arthur doesn’t like it.

He tells me he had put the undisturbed paint on his palette out several weeks earlier intending to do some work, but caught Covid. It’s still good for using, if a little sticky, and he shows me an exercise he learnt when he was a student at Camberwell. We mix Viridian Green with Alizarin Crimson until it is neither green nor red - it’s the perfect black. Just doing that bit is quite mesmorising and I appreciate how having this large surface to smear the paint across with the palette knife enables the undertones of the colour to be seen more clearly. We then mix our made black with white in various quantities to create a gradient. Then, taking a little from each we add either Colbalt Blue to create cool variations or Yellow Ochre to create warm. He encourages me to spread these on some small bits of paper and just think about what colour is next needed, what should go next to what. it’s very theraputic and he tells me he often does this to get himself started. Sometimes he says images will emerge. Sometimes he puts them around the studio, other times he paints over them. They’re on small bits of 90gsm square paper, which he says John Dobbs introduced him to and he giggles as he says it’s called a Maxi Pad and can be bought from Jacksons art.

We chat about artists and look through books, studying various paintings in detail, discussing the composition and colour, and that wonderful place between figuration and abstraction that we both enjoy. Arthur shows me how you can often find a square within in a composition and a trick for cutting a tiny window in a piece of paper to look at a detail of a painting to enable you to see it without distraction. There’s a painting in Arthur’s studio that he’s been working on for 30 years. I think it’s finished, he doesn’t, although he doesn’t know why.

Just as I’m about to leave he shows me his basement where he does his etching and printmaking - I am blown away by his range of skills, he tells me that he occasionally will attend a printmaking course locally. His basement, in complete contrast to his studio, is dark and mysterious. I feel it’s a kind of secret den where you could lose weeks of your life without noticing and / or plot to take over the world.

On the train home I find a Christmas card that Jane has snuck into my bag.

Life drawing from Vitoria Jinivizian’s workshop, charcoal on paper

9th January 2025, Victoria Jinivizian

I’ve met Victoria a couple of times - at my interview, a workshop and on zoom. She’s a very softly spoken and poetic sort of person, and her work feels a reflection of her personality. Victoria lives in a converted chapel in Wiltshire. Her home is filled with art that she has collected; everywhere there is drawing, a print, a painting. I use her loo at one point and get distracted by the beautiful work in there. She tells me that when she was a student at the Slade she would use her student loan to buy paintings and that every year she tries to buy a piece of art.

Victoria’s studio is also in her garden, although smaller than Arthur’s - but then so is her work. She also has a flat surface as a palette, but again much smaller, about the size of a chopping board. She has an easel, a desk and a chair - I’m assuming she sits down to paint. Victoria has what I would argue is every single small tube of paint in existence. Neatly arranged by colour - she has a draw full of reds, a box full of greens, yellows, blues, all the paints ever made. She knows them all intimately and tells me that she choses a limited palette to work from for her paintings. When I look at her palette I can see that around the edge are more small tubes of paint all arranged chromatically. There is barely any of her work so see, but on the wall is a painting that she is restoring for someone - she is very good at knowing exactly which colour is needed. There is also a drawing, which I admire and she says “oh no it’s terrible, I can’t believe it’s up” and an “old” painting of hers, which she sort of lets me compliment a bit.

Victoria has also made a wonderful mushroom soup and a lentil salad. We have a lovely chat over lunch at her carefully laid kitchen table with real linen napkins and beautiful crockery. It’s a different to my usual lunch on the floor or while driving or sometimes will teaching scenario. I feel very spoilt. Victoria has a daughter at university and we share the joys of being an artist and mother.

Victoria invited me to bring some of my own work along and so I share with her some paintings that have never been resolved - they’re all huge, one I had to remove from the stretcher to fit in my car. We roll it out on her living room floor and chat about it’s problems. It’s so helpful to have another perspective on it and interesting that, especially in a large painting, the bit that you think is the problem often isn’t and in actual fact the problem is elsewhere, usually hiding in plain sight. Victoria suggests I make a drawing from the painting, which I think is a genius idea and we discuss how to bring the colour together. She has a collection of small painted wooden swatches and arranges them on the floor with all the highly chromatic swatches in one line and the more muted ones in another, which she tells me are earth colours. She says she is trying to condense her own education into a few sentences so is hugely simplifying things, but wants to impress upon me that the earth colours can sit anywhere, quite comfortably in a painting, but that the highly chromatic ones need to be carefully considered. That, I think, is my ongoing problem. She also tells me that blue is always highly chromatic and there isn’t really an earth version of it - except maybe greys.

Drawing of boats in my sketchbook from Michael Weller’s plein air workshop, brush pen on paper

1st February 2025, Michael Weller

Michael lives and works from his home in Weymouth. He meets me from the station and takes me to a cafe for a sausage sandwich. He tells me “you should see as many artists as you can Charlotte, otherwise they might die, or go mad”. I say that statement will be my lasting memory from my visit. After a rush around Asda to grab a frozen pizza and some chocolate we go to Michael’s house. Michael’s life I feel fully reflects that of the dedicated artist. His work hangs on all the walls in his home, from the narrow hallway, to the bathroom. Paintings in progress are resting on the kitchen side, the piano and in front of the TV. There are paint finger prints on every doorframe and light switch, the buttons on his microwave and the dial on his oven. Newsprint spills from the draw under his TV. By each chair is a dusty pot of pastels. It feels as though you could be sitting anywhere and make a quick study mid way through your dinner or while watching TV.

Michael’s studio is also at the bottom of his garden. It is a tiny shed with one very small window. Inside there are a few permanent still life set ups with fruit in various stages of decay. One on a pink chair, another on a shelf that is no bigger than the picture ledges from Ikea, one on a table; I think I spot another on a stool, but there’s an empty crisp packet on it and I’m not sure if that’s just a discarded snack. Michael tells me that he used to rearrange the still life but that then he realised that he would happily return to the same landscape over and over again, painting it in different lights or from different positions, and so he treats the still lives the same way.

I didn’t notice what surface Michael uses to mix his paint on - there wasn’t much space, but I think he uses a palette knife for mixing - his painting has that uniform consistency. He tells me that he uses Jacksons student quality paints in Lemon Yellow, Cobalt Blue, Rose Madder and Zine White. He’s keen to emphasise the importance of the Jacksons brand so that the lemon yellow is bright and punchy (that’s what my student lemon is like) and not subtle (like the Michael Harding one). He says you can reach most colours with those. I think about the colour wheel and my discussions with James and I can see that those colours would indeed make most other colours - in fact they’re a bit like the CMYK colours used for printing (without the K - which is blacK). Michael tells me that he prefers Zinc White to Titanium because it doesn’t corrupt and desaturate the colour so much. Michael’s paintings are indeed colourful, but so carefully balanced and he tells me that he is always careful to mix a small amount of the complimentary with any colour that he makes in order to desaturate it slightly and enable it to sit with the others. I ask what he thins his paint with and he says he mostly doesn’t but that if you do thin it just use a tiny dip on the end of the brush (a memory of pouring my medium concoction into my microwave curry tubs to create a more fluid paint pops into my head at this point).

Michael wonders if I would like to do some printing and if it might be useful for my “line”. He shows me how to make a drypoint etching and back in his living room I attempt to draw him. The etching cardboard is white and the drypoint scratches the surface of it - it’s almost impossible to see what mark I’m making, which is not helped by there not being any lights on and it now being late afternoon in winter. It is a fascinating process and I remember that Arthur also makes prints in his world domination basement - perhaps I should do more of this…

Drawing in my sketchbook of Richmond lock from John Dobbs’ plein air workshop, graphite on paper

17th February 2025, John Dobbs

A few weeks later I visit John Dobbs. Like Michael Weller, John was also an NEAC scholar a long time ago. He tells me how Arthur Neal helped him a lot and he still keeps in regular contact with him. John is in Rickmansworth in North London. He is in the middle of renovating his own house, which is on a hill so that the back of it is upstairs but also downstairs at the same time. He has a neat little extension underneath the upstairs downstairs bit at the back where he makes his own frames and has a press for printmaking too, Arthur’s old press it turns out. He shows me lino cuts and wood cuts and etchings. John is very tall and can’t stand up in this space without hunching, but he can sit. It’s perfect for me. He tells me he used to do all his work in this too low for him space but now he has a cabin in his garden up the hill.

We go there next and it is wonderful. Natural light floods in from all directions and because it’s up the hill the view is beautiful and is surrounded by nature. He has a huge mirror and I wonder if he’s making a portrait, except that I’ve never seen him paint portraits. Later as we’re discussing not being able to see your work for looking he tells me “that’s what the mirror is for”. He looks at his work in the mirror to get a fresh perspective. This is a brilliant idea that I plan to steal, if I can find space for a mirror.

John is also a running coach and he makes a healthy lunch for us of stuffed peppers and we look at books and he talks to me about Diebenkorn, who Arthur Neal introduced him to. John tells me he is really interested in the relationships between colours on the surface, how one colour reads next to another, but as a former engineer he is also interested in the construction of what he is painting three dimensionally - what’s in the foreground and what is behind. It’s a bit of a contradiction, and he wonders if it’s impossible. I say it’s just a very narrow sweet spot that is a nightmare to reach, but that’s what makes it worth aiming for. He’s working on a large painting of a building site called Digger Land and he’s not sure if he’s overworked bits of it.

John also has a large flat table top type surface as a palette. He is the first artist I meet who mixes his paints with a brush - rejoice! He has a massive plant pot filled with thinners where his used brushes are all neglected and probably slowly eroding. I feel better about my own brush cleaning laziness. He does use decent paint, telling me that student quality is just a false economy because they’re loaded with fillers. He has bought himself an orange for his digger land painting because “you can’t make a decent orange.” I don’t know if I agree, but now I wonder if I am just not as sophisticated at noticing the difference.

John has millions of sketchbooks, Maxi Pads in fact, of drawings he’s made in Africa, he makes paintings of animals and landscapes from these. The sketches are just very loose pencil studies. I ask him about the colour and he shows me how he writes notes about the lighting and the colour to remind him and he works from those. There’s a vase of flowers in the corner. He paints a lot flowers too and shows me how the couple of random bits of A4 print outs pinned behind are actually there to create a bit of a background and I look at his painting and can see that it is very effective in assisting those colour relationships that he is so interested in.

Experiments with my plant still life, development from Clare Haward’s online still life workshop, oil and oil stick on paper with mono printed elements

19th February 2025, Clare Haward

Two days later I visit Clare Haward. Like James and Victoria, Clare is one of the people who interviewed me for the scholarship and I’ve met her on zoom a few times too. Her still life workshop inspired a terrible painting that I am still wrestling with. Somehow she managed to spark an interest in plants that I’ve never had before and her patient and inspirational teaching lit a sort of stubborn fire in me that will not go out.

Clare works in the most wonderful building in Dulwich - Stanley Arts. Designed and built by William Stanley in the early 1900’s as a public arts, culture and entertainment space, it fell into disrepair and was rescued by a community initiative about ten years ago. As well as having a studio here, Clare has helped organise and run the space and takes me on a tour. There are beautiful crafted details throughout the building - gorgeous emerald and copper green tiles that some people are discussing restoring as we pass through a room, carved wooden banisters and a spectacular hall where Clare holds life drawing classes. I am lost almost immediately and when Clare shows me into her studio I’m sure I would never be able to find it again!

The light in Clares studio is perfect, clear and diffused with wonderful high ceilings. Work is stacked around the space and there’s an area slightly separated with more work, props and materials. Clare has a beautiful easel that she tells me she bought with a grant of some sort, which I can’t quite remember. On the walls are a mixture of drawings, a couple of print outs of photographs from her childhood, and monoprints that she’s taken from paintings. These small scraps of shapes are fascinating and I love how she can see potential in the smallest accidental mark, it’s almost as though she’s searching for clues in her own work.

We chat instantly and Clare talks to me about a time when she decided to start making her own paints using pigment and linseed oil (she doesn’t anymore). She shows me how to do this, it’s very therapeutic grinding down the pigment and adding the oil and we do this together for a while while we chat. She shows me how each pigment has different qualities, some need more grinding than others. Immediately I want to mix the ground pigments together (rather than mixing the finished paints together) to see what will happen and Clare is totally open to us trying this, which we do, creating a sort of deep brown colour. We start chatting about white paint and Clare shows me several different whites, including a lead white that one of her students bought from a car boot sale. We spend a lovely relaxing time mixing our pigment made paint with different whites and just smearing it onto a canvas. It’s very calming talking and playing around with paint. Clare uses a flat surface to mix her paint - a big white slab, possible from a fridge or a cupboard door. She shares my hatred of cleaning brushes and tells me how someone told her to just put them straight into water when they’re covered in paint, which sort of pauses the whole drying process and then you just give them a wipe when you next want to work with them.

Clare takes me on another adventure in her building to the kitchen where we make rolls for our lunch, sitting outside in the courtyard to eat them and I steal a sticker that says “Wednesday” on it from the kitchen as a reminder of my visit. After lunch Clare introduces me to her partner Gareth Brookes who is a graphic novelist. His studio is next door to her’s but about a quarter of the size, with just enough space for a desk and some shelves. Later I look through some of his work and am fascinated by the craftmanship that goes into each of his books. One of them is made using the technique I remember as a child of putting colour onto paper and covering it in wax crayon, then scratching it away with a coin. Except this is done with care and commitment so that each drawing must take hours. Another is made using embroidery and another using lino cut. They are beautiful works of art.

Before I leave Clare and I chat about some of the work that is around the studio, which is for her upcoming show with fellow NEAC artist Grant Watson. They’ve chosen pieces of each others work to include so that their show is curated collaboratively, recognising that another artist can often see merits in your work that you might have overlooked yourself. I feel really honoured to be able to talk with Clare about her work like this, although slightly conscious that I’m not really worthy!

Man & Plant, finished painting, oil on canvas, sent to Peter Clossick for advice before committing to leave it be

9th April 2025, Peter Clossick

Just before Easter I visit Peter Clossick at his home on a leafy street in Blackheath. We have a cup of tea and a chat at his kitchen table by the window, where a string of origami dragons are hanging, I admire them and he tells me his grandson likes to make them. Peter grew up in Kings Cross and tells me a story of being a teenager in the 1960s and attending life drawing classes at the Working Men’s College. He took to drawing instantly and used to sell these life drawings to his his fellow teenage students at the grammar school he attended. One day he was caught doing so and expelled for selling explicit drawings! He somehow ended up studying shoe design at Leicester Polytechnic, working as a freelance shoe designer very successfully for several years before studying art at Camberwell and then Goldsmiths.

We chat about painting - Peter used to run the Fine Art degree course at Oxford Brookes University, where I did my foundation year. Peter talks about painting as a language and says that unlike words painting is not a linear language, but rather it is circular, and that every end should also be a beginning. I find this such a helpful statement to take away and try and keep it in my mind in the weeks that follow.

Peter’s house is full of art. Works he’s collected over the years, including an etching by Euan Uglow, as well as lots of his own paintings made over his lifetime; it’s interesting to see his style evolve into the thick impasto pieces he is so well known for, they have an Auerbach quality and Peter tells me they shared a model for a time. Peter’s front room is dedicated to storing his work and I’m reminded of Arthur Neal’s house whose front room is also dedicated to storing paintings. We go to his studio next. It’s a sort of lean-to attached to his house; a lovely long but narrow space. Plastered over the walls are hand written statements and newspaper cut outs, a mixture of general painting advice and interesting articles. They’re full of philosophical wisdom and I’m again reminded or Arthur Neal wondering when his work is finished, introducing me to Diebenkorn's rules, and mixing up colours as a way to get going, and I feel comforted that every artist I have met, regardless of age or experience, seems to be searching for the same thing, a clue within themselves perhaps, a map into their own mind.

Peter’s paint palette is an old camping table, it’s so thick around the edges with years and years of paint that I doubt it would ever fold down again. He uses the whole surface of the table and I am again comforted by the lack of anything fancy, but rather the importance of just finding what works. His paintings are so thick they are almost three dimensional. We talk a bit about the practicalities of this and the underneath layers needing to be dry before more paint is added otherwise they can crack. There is a chase longue and a heather in his studio and Peter tells me he works solely from life. He talks about each session on a painting being a completely new beginning and that a piece might change completely from one sitting to another and that that is part of it. I think back to his idea of painting being a circular language and this fits. I really want to touch the paintings and Peter is fine with that. They are so tactile! Some are varnished, which makes the colours deeper and richer. They all feel as though the paint could stand up and walk out of the frame, like a Giacometti sculpture. I go home and a few weeks later I email Peter about two pieces I’m working on for the NEAC show. I’m really excited by them but know they are risky - which is why I’m excited by them. He tells me to leave them as they are and start something new with the same intentions, which turns out the be great advice.

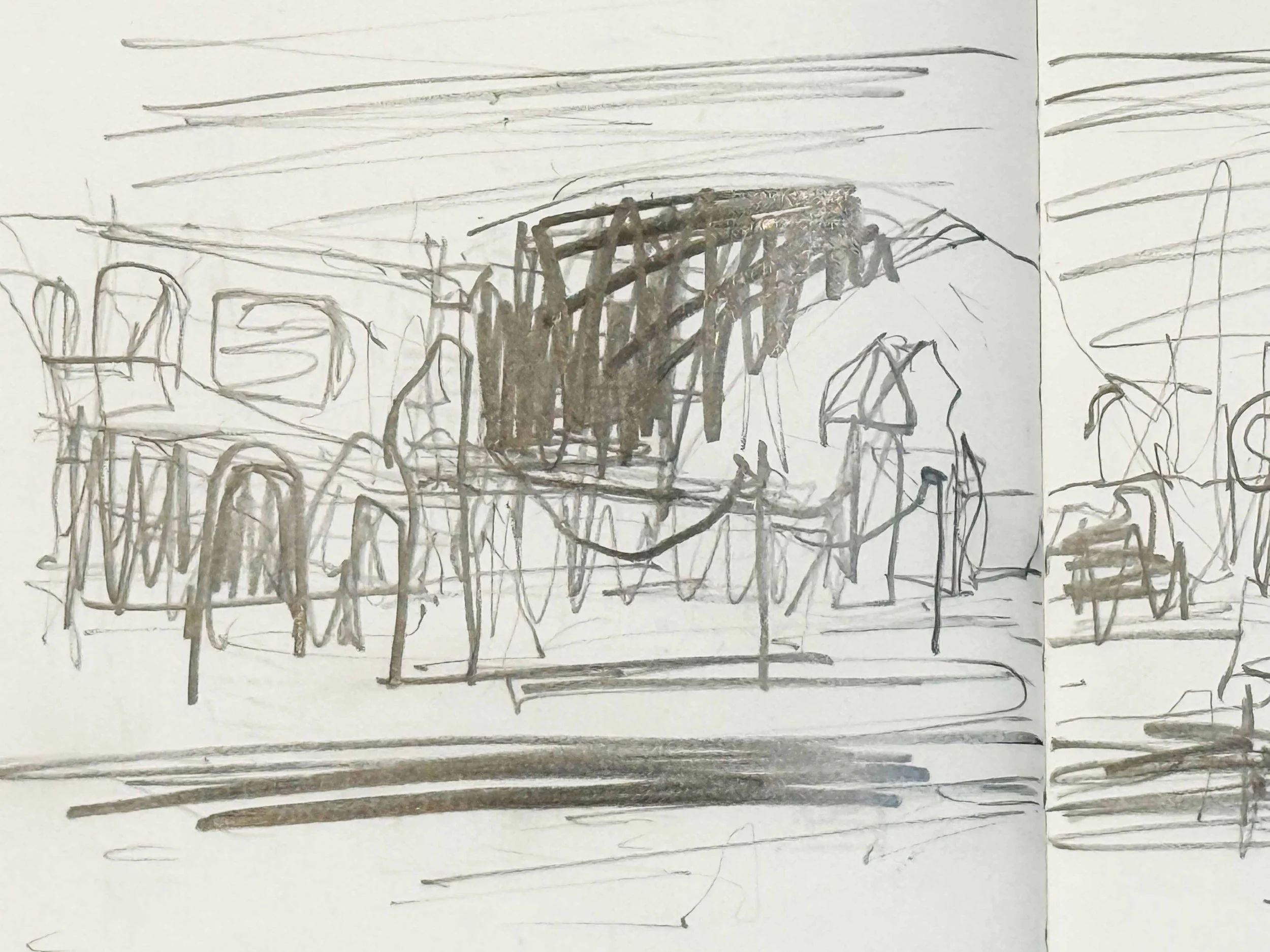

Easter experiments responding to flowers left on my doorstep by a florist friend. Torn up and collaged gelli prints made with oil paint, following my visit to Grant Watson

10th April 2025, Grant Watson

The following day I am back in London, this time in Stockwell to visit Grant Watson who is having a two person show with Clare Haward, Clare’s told me Grant is lovely and I really enjoy his work - it’s tactile and painterly, playful but mature at the same time. I’m looking forward to seeing how he makes it. Grant’s studio is in a fairly modern building that houses a number of artist studios. He tells me that he gets together with a few other residents every afternoon for a cup of coffee and a chat, which is a nice way of reflecting. His studio space is a large white room with brilliant lighting, lots of space and high ceilings. There’s a sort of divide where past work is stacked and he talks about how his style has evolved enormously over his career.

It’s quite a clinical room in many ways, but Grant has softened it with his presence and practice. On the walls are works in progress surrounding the whole space, so that it’s possible to put a bit of paint here and there on several paintings at once. I like this approach, it feels relaxed and spontaneous. There’s a large white trolly in the middle of the room that he uses as his paint palette. It’s covered in layers and layers of old paint and when I look closer I see that on the lower shelf is a bit of laminated chipboard, which I can tell has acted as a paint palette in the past because it is thick with old paint and has a discarded paint brush dried stuck on it. I love this. Grant uses large tins of paint in just a few colours - a blue, red yellow and white (although I didn’t notice which specific hues) from what I can tell. Most have their lids off and he’s poured water into them to prevent the paint from drying out. He tells me he just tips this away when he wants to paint and then he shows me his very well used brushes also sitting in water, that he casually wipes off, dips in a bit of paint and applies to one of the canvases on the wall.

He potters about showing me things and making tea and some rich tea biscuit. Casually vaping as he goes and we chat a bit about our kids - we both have daughters named Daisy, and Grant tells me he also works at a special needs school one day a week. He talks a bit about some of the students inspirational work and also some of the art materials he’s stumbled across there, including a painting medium that he shows me. He likes it because it dries overnight and he can carry on working the next day, but he’s not especially sure what it is. I really like his slightly serendipitous approach and lack of concern for rules. I imagine he makes a great teacher as well as artist.

There’s an L shaped table in the middle of the room and Grant tells me how he spent about three months recently just drawing and making gelli prints. He said it was really cathartic and helped him loosen up again. He shows me how to make a charcoal drawing and then transfer this onto the gelli plate, then drizzle acrylic and roller it across so that when we print from it both the charcoal and the paint are picked up. I am instantly hooked and get out my pencil case and try out using my brush pens, paint pens and Grant’s coloured soft pastels to see what will happen. We do this back and forth for a while, chatting as we go and I like the discoveries I make in doing this. He says he doesn’t really know what he’s doing with it all but he enjoys the experimentation. He wonders if he should run a course like this with the NEAC. I say he should. I make four prints inspired by the mug of tea he made me and Grant says “you could flog those”.